A Commencement Speech for the Doomed

in Our Age of American Decline Win or lose, Donald Trump has cast a shadow across our democracy. The class of 2016 faces a grim, uncertain future By Tom Engelhardt / Tom Dispatch Graduates of 2016, don’t be fooled by this glorious day. As you leave campus for the last time, many of you already deeply in debt and with a lifetime of payments to look forward to, you head into a world that’s anything but sunny. In fact, through those gates that have done little enough to protect you is the sort of fog bank that results in traffic pile-ups on any highway. And if you imagine that I’m here to sweep that fog away and tell you what truly lies behind it, think again. My only consolation is that, if I can’t adequately explain our American world to you or your path through it, I doubt any other speaker could either. Of course, it’s not exactly a fog-lifter to say that, like it or not, you’re about to graduate onto Planet Donald — and I don’t mean, for all but a few of you, a future round of golf at Mar-a-Lago. Our increasingly unnerved and disturbed world is his circus right now (whether he wins the coming election or not), just as in the Philippines, it’s the circus of new president Rodrigo Duterte; in Hungary, of right-wing populist Viktor Orbán; in Austria, of Norbert Hofer, the extremist anti-immigrant presidential candidate who just lost a squeaker by .6% of the vote; in Israel, of new defense minister Avigdor Lieberman; in Russia, of the autocratic Vladimir Putin; in France, of Marine le Pen, leader of the right-wing National Front party, who has sometimes led in polls for the next presidential election; and so on. And if you don’t think that’s a less than pretty political picture of our changing planet, then don’t wait for the rest of this speech, just hustle out those gates. You’ve got a treat ahead of you. For the rest of us lingerers, it says something about where we all are that, once through those gates, you’ll still find yourself in the richest, most powerful country around, the planet’s “sole superpower.” (USA! USA!) It is, however, a superpower distinctly in decline on — and this is a historic first — a planet similarly in decline.

How Trumpian Is American Authoritarianism?

In its halcyon days, Washington could overthrow governments, install Shahs or other rulers, do more or less what it wanted across significant parts of the globe and reap rewards, while (as in the case of Iran) not paying any price, blowback-style, for decades, if at all. That was imperial power in the blaze of the noonday sun. These days, in case you hadn’t noticed, blowback for our imperial actions seems to arrive as if by high-speed rail (of which by the way, the greatest power on the planet has yet to build a single mile, if you want a quick measure of decline). Despite having a more massive, technologically advanced, and better funded military than any other power or even group of powers on the planet, in the last decade and a half of constant war across the Greater Middle East and parts of Africa, the U.S. has won nothing, nada, zilch. Its unending wars have, in fact, led nowhere in a world growing more chaotic by the second. Its militarized “milestones,” like the recent drone-killing in Pakistan of the leader of the Taliban, have proven repetitive signposts on what, even in the present fog, is surely the road to hell. It’s been relatively easy, if you live here, to notice little enough of all this and — at least until Donald Trump arrived to the stunned fascination of the country (not to speak of the rest of the planet) — to imagine that we live in a peaceable land with most of its familiar markers still reassuringly in place. We still have elections, our tripartite form of government (as well as the other accoutrements of a democracy), our reverential view of our Constitution and the rights it endows us with, and so on. In truth, however, the American world is coming to bear ever less resemblance to the one we still claim as ours, or rather that older America looks increasingly like a hollowed-out shell within which something new and quite different has been gestating. After all, can anyone really doubt that representative democracy as it once existed has been eviscerated and is now — consider Congress exhibit A — in a state of advanced paralysis, or that just about every aspect of the country’s infrastructure, is slowly fraying or crumbling and that little is being done about it? Can anyone doubt that the constitutional system — take war powers as a prime example or, for that matter, American liberties — has also been fraying? Can anyone doubt that the country’s classic tripartite form of government, from a Supreme Court missing a member by choice of Congress to a national security state that mocks the law, is ever less checked and balanced and increasingly more than “tri”? In the Vietnam era, people first began talking about an “imperial presidency.” Today, in areas of overwhelming importance, the White House is, if anything, somewhat less imperial, but only because it’s more in thrall to the ever-expanding national security state. Though that unofficial fourth branch of government is seldom seriously considered when the ways in which our American world works are being described and though it has no place in the Constitution, it is increasingly the first branch of government in Washington, the one before which all the others kneel down. There has, in this endless election season, been much discussion of Donald Trump’s potential for “authoritarianism” (or incipient “fascism,” or worse). It’s a subject generally treated as if it were some tendency or property unique to the man who rode a Trump Tower escalator into the presidential race to Neil Young’s “Rockin’ in the Free World,” or perhaps something from the 1930s that he carries in his jacket pocket and that his enthusiastic white working class followers are naturally drawn to and responsible for. Few bother to consider the ways in which the foundations of authoritarianism have already been laid in this society — and not by disaffected working class white men either. Few bother to consider what it means to have a national security state and a massive military machine deeply embedded in our ruling city and our American world. Few think about the (count ’em!) 17 significant intelligence agencies that eat close to $70 billion annually or the trillion dollars or more a year that disappears into our national security world, or what it means for that state within a state, that shadow government, to become ever more powerful and autonomous in the name of American “safety,” especially from “terrorism” (though terrorism represents themost microscopic of dangers for most Americans). In this long election season, amid all the charges leveled at Donald Trump, where have you seen serious discussion of what it means for the Pentagon’s spy drones to be flying missions over the “homeland” or for “intelligence” agencies to be wielding the kind of blanket surveillance of everyone’s communications — from foreign leaders to peasants in Afghanistan to American citizens — that, technologically speaking, put the totalitarian regimes of the previous century to shame? Is there nothing of the authoritarian lurking in all this? Could that urge really be the property of The Donald and his followers alone? Perhaps it would be better to see Donald Trump as a symptom, not the problem itself, to think of him not as the Zika Virus but as the first infectious mosquito to hit the shores of this country. If you need proof that he’s at worst a potential aider and abettor of authoritarianism, just take a look at the rest of our world, where the mosquitoes are many and the virus of right-wing authoritarianism spreading rapidly with the rise of a new nationalism (that often goes hand in hand with anti-immigrant fervor of a Trumpian sort). He is, in other words, just one particularly bizarre figure in an increasingly crowded room. Bursting Bubbles and Melting Ice Caps If, as the first openly declinist presidential candidate, it’s The Donald’s job to make America great again, and if, despite its obvious wealth and military strength, the heartlands of the U.S. do look ever more Third World-ish, then consider the rest of the planet. Is there any place that doesn’t look at least a little, and in a remarkable number of cases, a lot the worse for wear? Leave aside those parts of the world from Afghanistan to Syria, Yemen to Libya, Nigeria to Venezuela that increasingly have the look of incipient or completely failed states. Consider instead that former Cold War enemy, that “Evil Empire” of a previous incarnation, the once-upon-a-time Soviet Union, now Vladimir Putin’s Russia. It has made it to the top of the American military’s list of enemies. And yet, despite its rebuilt military and still massive nuclear arsenal, the superpower of yesterday is now a rickety petro-state with a restive population, a country that is neither great, nor rising, and may in fact be in genuine trouble. Yes, it has been aggressive in its borderlands (though largely in response to a sense of, or fear of, being aggressed upon) and yes, it is an authoritarian land, but no longer is it the planet’s second superpower or anything remotely like it. Its future looks, at best, insecure, at worst bleak indeed. Even China, the only obvious rising power on the planet (now that countries like Brazil and South Africa are falling by the wayside), that genuine economic powerhouse of the last decade, has seen its economy slow significantly. In such a moment, who knows what one burst bubble, real estate or otherwise, might do there? An economic meltdown in the People’s Republic, with an expanding middle class that still remains small compared to its peasant masses, and an unparalleled record of peasant revolts extending back centuries, could prove an ominous event. And mind you, graduates of 2016, that’s just to begin a discussion of the stresses on a planet whose ice caps are melting, sea levels rising, waters warming, forests drying, fire seasons expanding, storms intensifying, and temperatures rising (while petro-states, frackers, and giant oil companies keep pumping fossil fuels in ever more inventive ways as if there were — and don’t just think of it as a figure of speech — no tomorrow). In such a situation, no place, including this country, is too big to fail. And on such a helter-skelter planet, who will be there to bail out the too-big-to-fail states or anyone else? Judging by none-too-big-to-fail countries like Libya, Yemen, and Syria that have already essentially collapsed, the answer might be no one. Decades ago, in the mid-1970s, in the first book I ever wrote, I labeled our American world “beyond our control.” Little did I know!

American Magical Realism

Now, let’s turn to you, graduates of 2016, and while we’re at it, to what we’re still calling an “election.” I’m talking about the roiling, ever-expanding phenomenon that now fills our TV screens and the “news” more or less 24/7 and for which, whatever he’s done and whomever he’s insulted, Donald Trump cannot all by himself be held to blame. There is, to my mind, one question that makes what we call “election 2016” of paramount interest, even if we seldom bother to think about it: What the hell is it? We still refer to it as an “election,” of course, and on November 4th millions of us will indeed enter voting booths and opt for a candidate. Still, don’t tell me that, in any normal sense, this is an election, this weird money machine pouring billions and billions of dollars into the coffers of media barons, this endless, overblown, onrushing event with its “debates” and insults and anger and minute-by-minute polling results and squadrons of talking heads yammering away about nothing in particular, this bizarre stage set for an utterly unfiltered narcissist and reality-show host and casino owner and bankruptee and braggart and liar and fantasist and womanizer and… well, you know the list better than I do. Yes, it will put someone in the Oval Office next January and fill Congress with the usual set of clashing deadheads, but in any past sense of the word, an election? I don’t think so. Don’t tell me it isn’t something new and different. Everyone knows it is. But what, exactly? I have no idea. It’s clear enough, however, that our American system is morphing in ways for which we have no names, no adequate descriptive vocabulary. Perhaps it’s not just that we have no clear bead on what’s going on, but that we prefer not to know. Whether Donald Trump wins or not, rest assured that we all have an education ahead of us. This, after all, is our world now. You have no choice but to leave these grounds and neither, in a sense, do your parents, grandparents, siblings, friends, the whole lot of us. Whether we like it or not, we’re all being shoved unceremoniously into an American world that’s changing in unnerving ways on a planet itself in transformation. Which brings me to the task ahead of your generation (not mine), as I imagine it. After all, I’m almost 72 years old. I’m superannuated. When something goes wrong on my computer I genuinely believe myself doomed, grieve for the lost days of the typewriter, and then, in despair, call my daughter. And if I can’t even grasp the basics of the machine I now live on much of the time, how likely is it that I — and my ilk — can grasp the world in which it’s implanted? As I see it, you’ve been attending classes, studying, and preparing all these years for just this moment. Now, it’s your job to step into the fog-bound landscape beyond these gates where the pile-ups are already happening and make sense of it for the rest of us. Soon, graduates of 2016, you will leave this campus. The question is: What can you do for yourself and the rest of us then? Here’s my thought: to change this world of ours, you first have to name (or rename) it, as any magical realist novelist from Gabriel García Márquez on has long known. The world is only yours when you’ve given it and its component parts names. If there’s one thing that the Occupy Wall Street movement reminded us of, it was this: that the first task in changing our world is to find new words to describe it. In 2011, that movement arrived at Zuccotti Park in lower Manhattan calling the masters of our universe “the 1%” and the rest of us “the 99%.” Simply wielding those two phrases brought to the fore a set of previously half-seen realities — the growing inequality gap in this country and the world — and so briefly electrified the country and changed the conversation. By relabeling the mental map of our world, those protesters cleared some of the fog away, allowing us to begin to imagine paths through it and so ways to act. Right now, we need you to take these last four hard years and everything you know, including what you weren’t taught in any classroom but learned on your own — your experience, for instance, of your education as a financial rip-off — and tell those of us in desperate need of fresh eyes just how our world should be described. In order to act, in order to change much of anything, you first need to give that world the names, the labels, it deserves, and they may not be “election” or “democracy” or so many of the other commonplace words of our past and our present moment. Otherwise, we’ll all continue to spend our time struggling to grasp ghostly shapes in that fog. Now, all you graduates, form up your serried ranks, muster the words you’ve taken four years to master, and prepare to march out of those gates and begin to apply them in ways that your elders are incapable of doing. Class of 2016, tell us who we are and where we are.

Tom Engelhardt is a co-founder of the American Empire Project and the author of The United States of Fear as well as a history of the Cold War, The End of Victory Culture. He is a fellow of the Nation Institute and runs TomDispatch.com. His latest book is Shadow Government: Surveillance, Secret Wars, and a Global Security State in a Single-Superpower World.

|

-

-

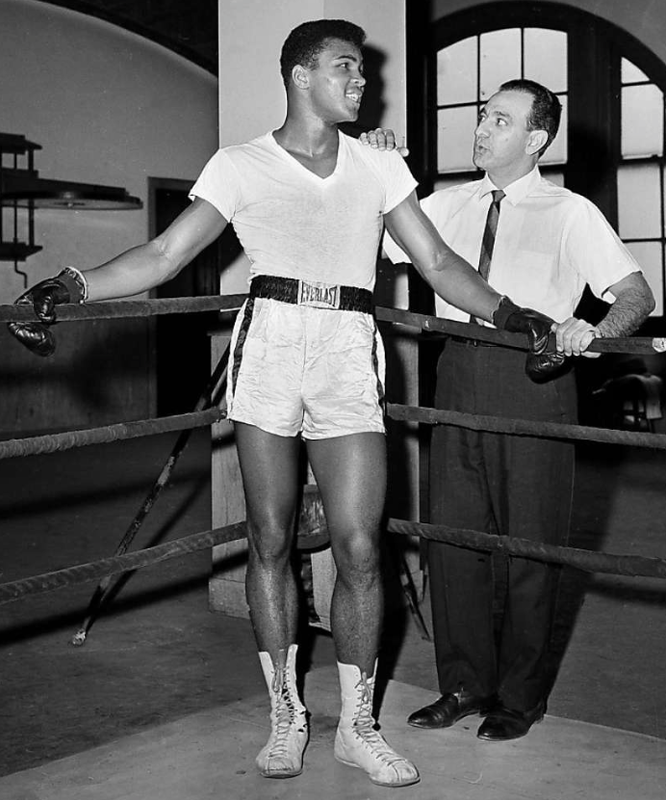

Muhammad Ali Was a Hero,

but His Enemies Have a Legacy Too

by Matt Taibbi Rolling Stone

Pentagon learned from the epic mistake of making a martyr of the world's most gifted and famous athlete

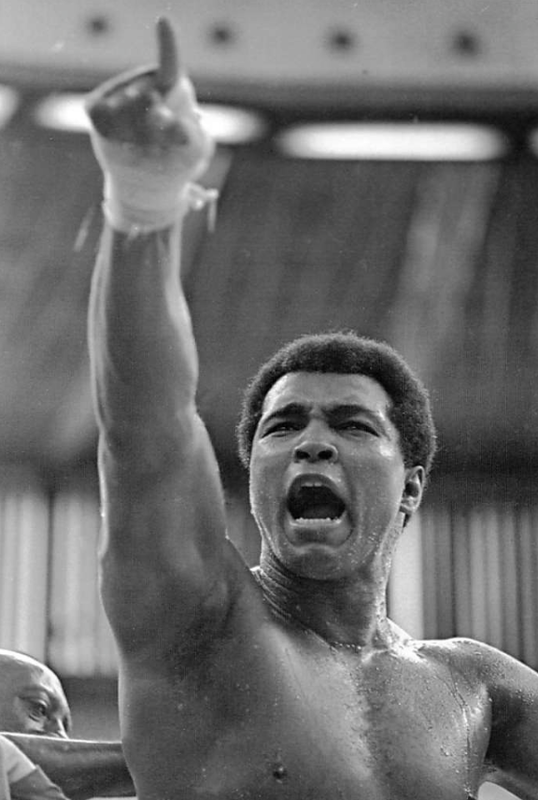

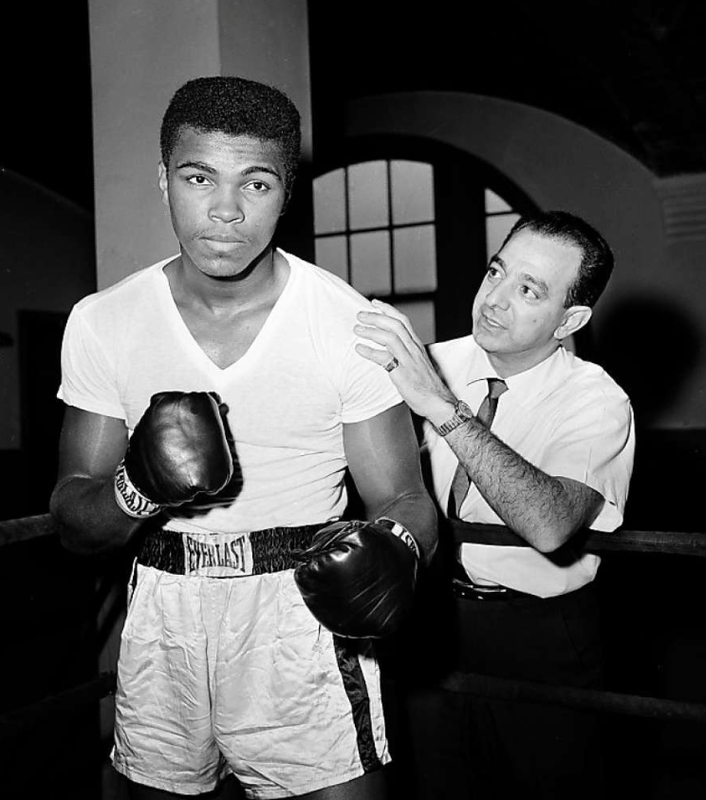

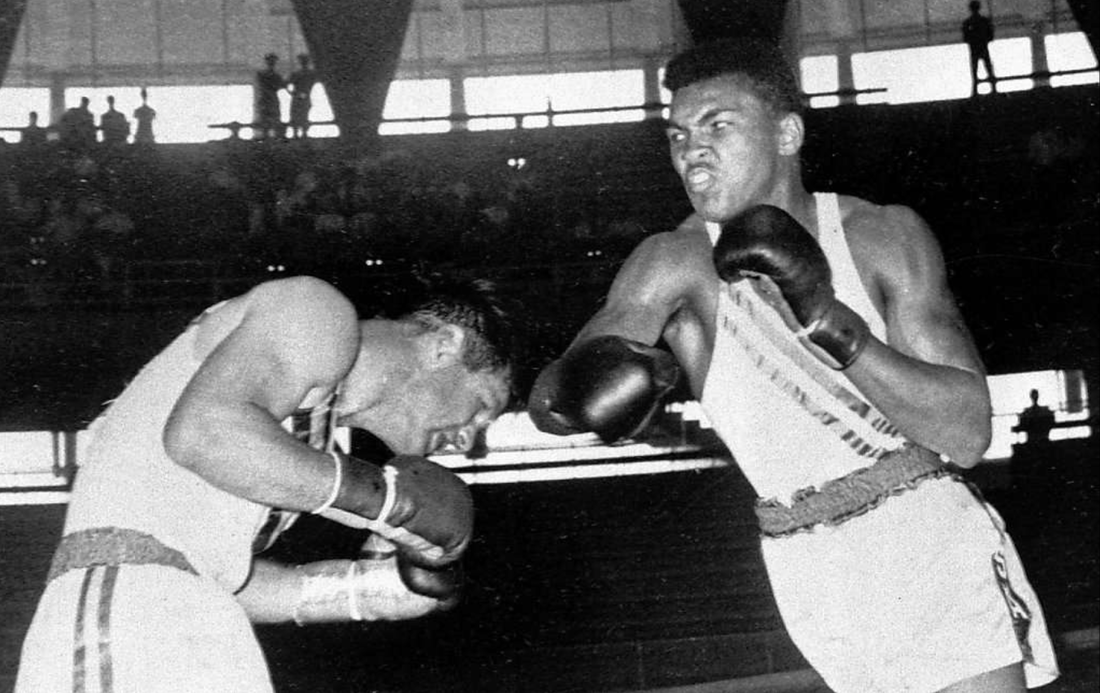

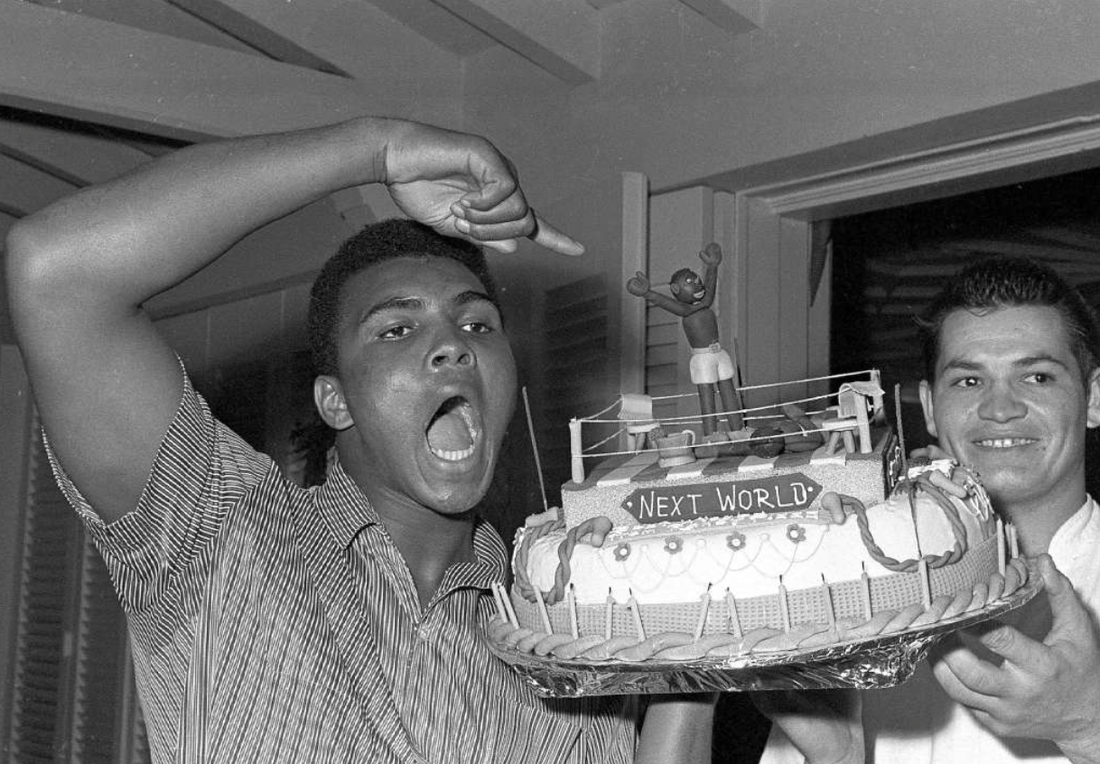

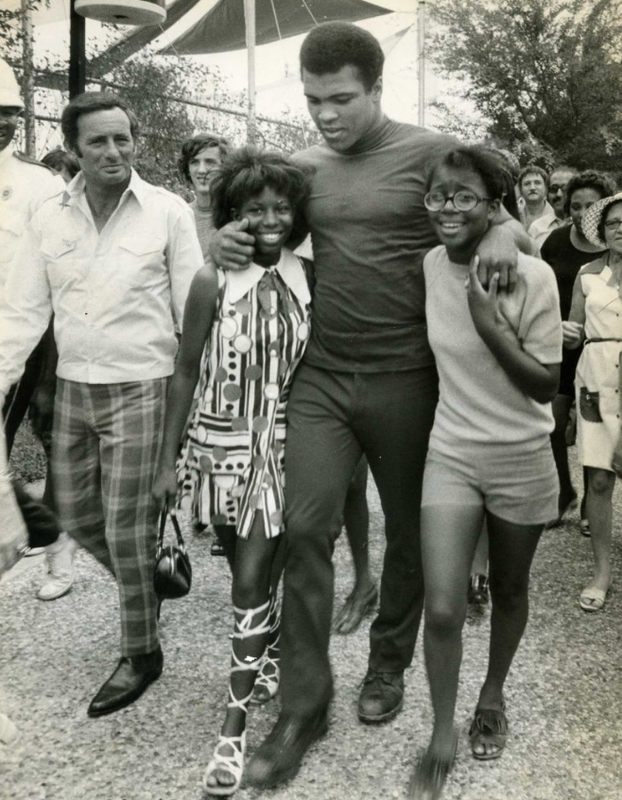

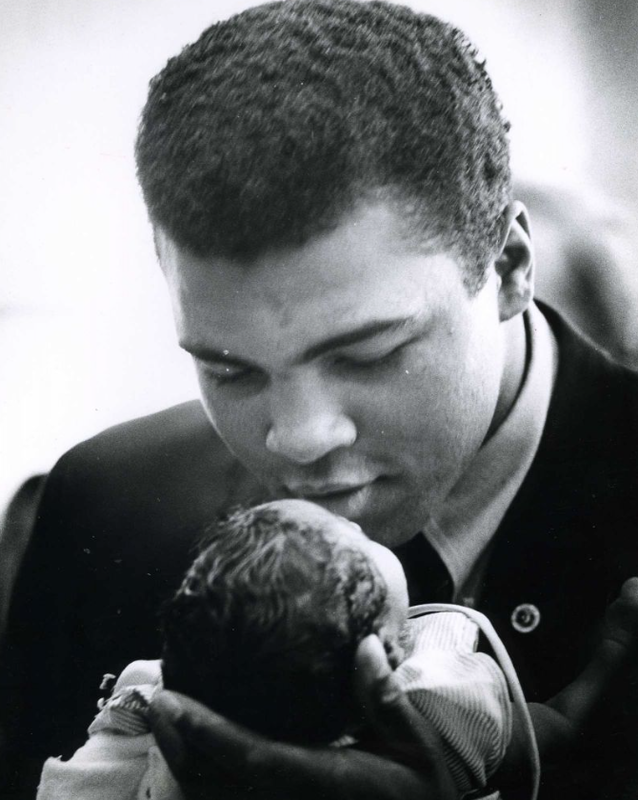

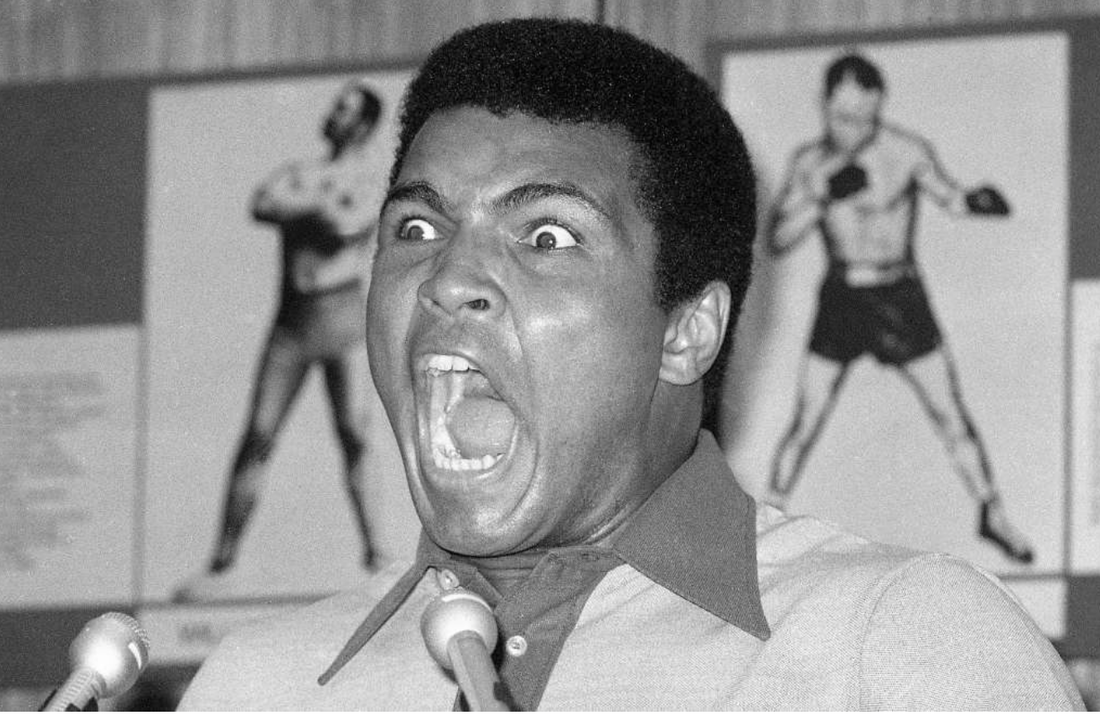

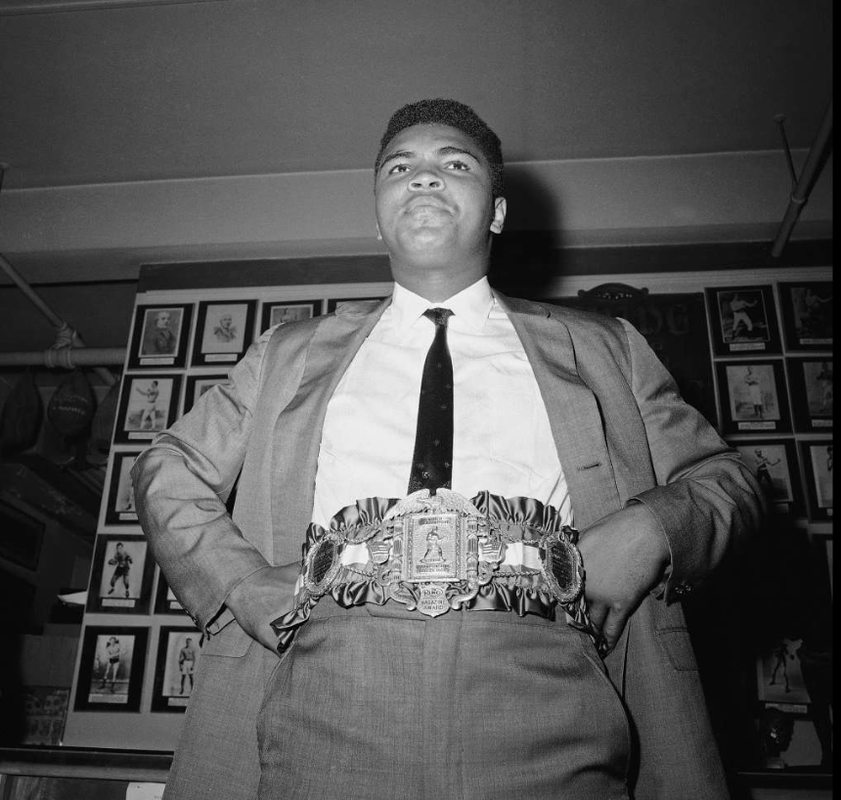

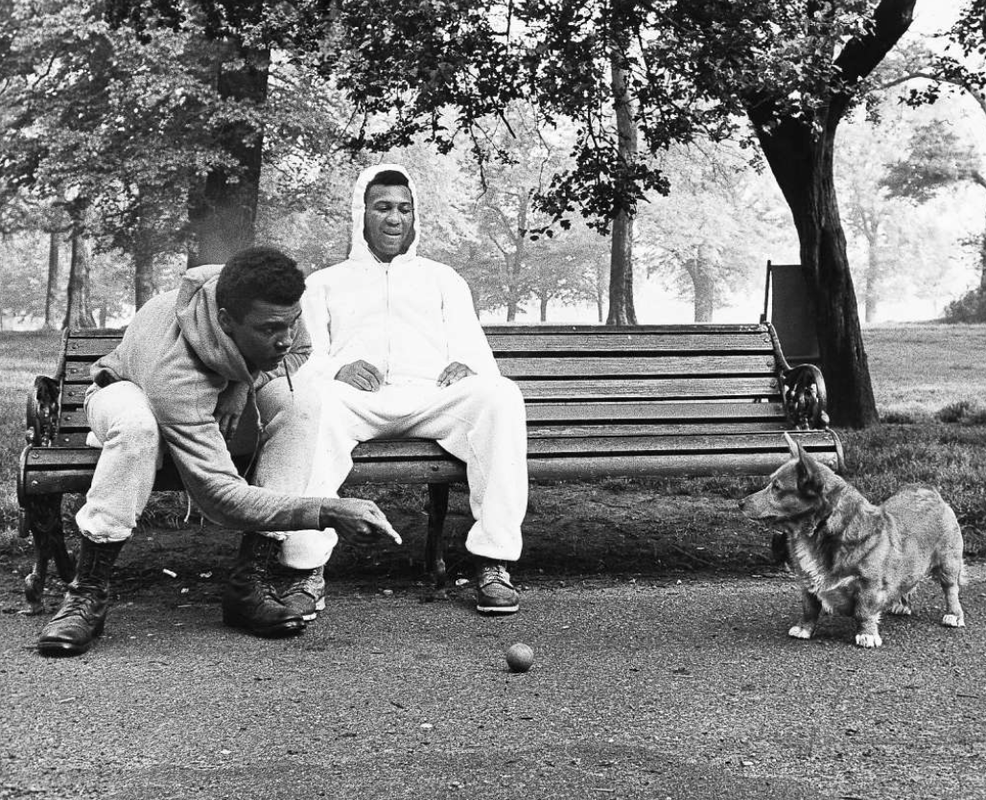

When I was growing up, it was impossible to imagine anyone cooler than Muhammad Ali. He had the perfect looks of a rock star, was hilariously funny, and was beautiful to watch in the ring. My friends and I used to pop in tapes of his fights and double over laughing watching his opponents flail about in search of that infuriatingly pretty face of his.

As is the case with many people who are reflecting on Ali's legacy right now, Ali for me later in life also defined what it meant to stand on a principle. The story of how he defied the government and risked jail because he refused to kill on command was easy even for a young person to understand.

So I was saddened to hear of his death earlier this weekend. It's unlikely we'll ever see anyone like Ali again, and not just because he was a billions-to-one marvel of physical and mental gifts.

It's also because his enemies learned from the mistake they made, and spent a generation making sure that the next of his ilk, in the unlikely event that he or she ever comes along, won't become so powerful a dissenting influence.

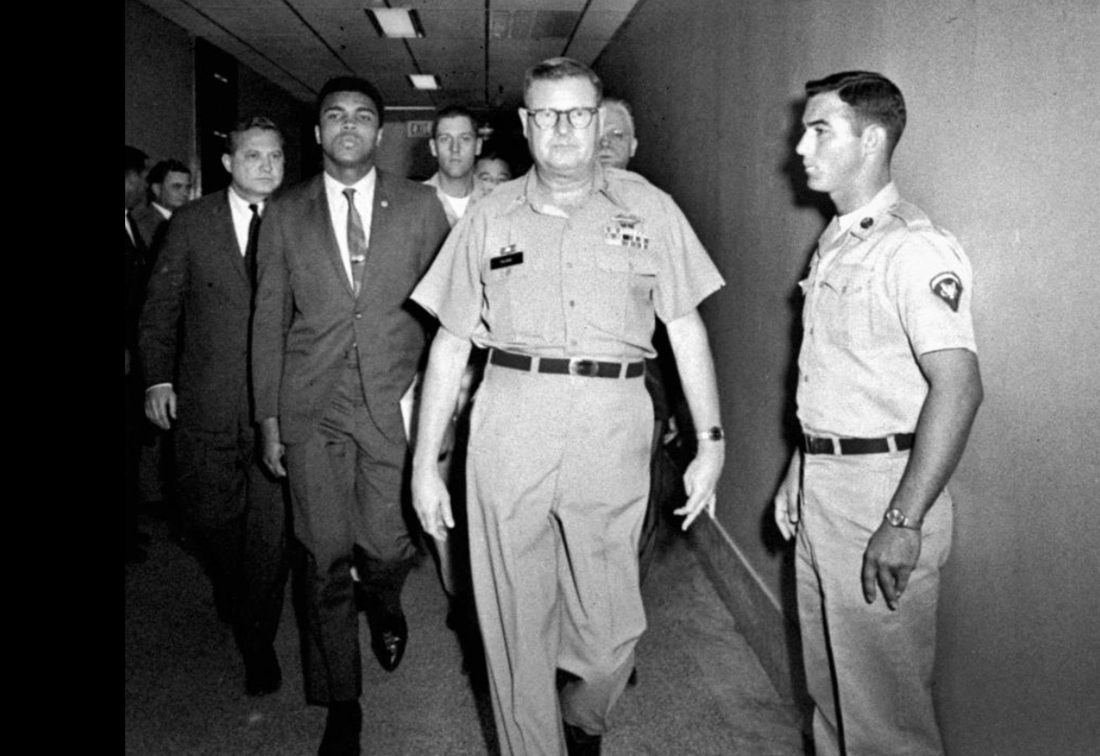

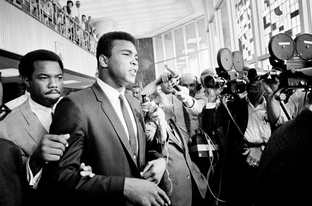

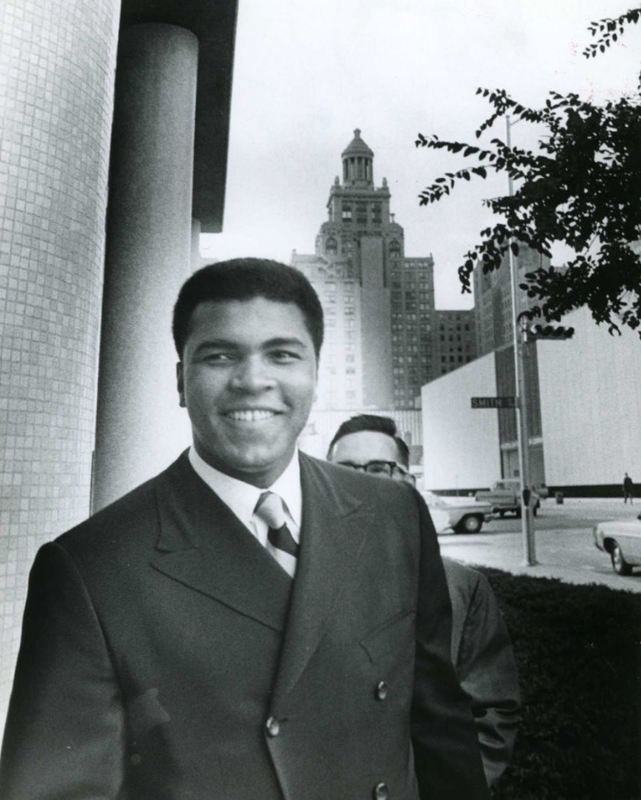

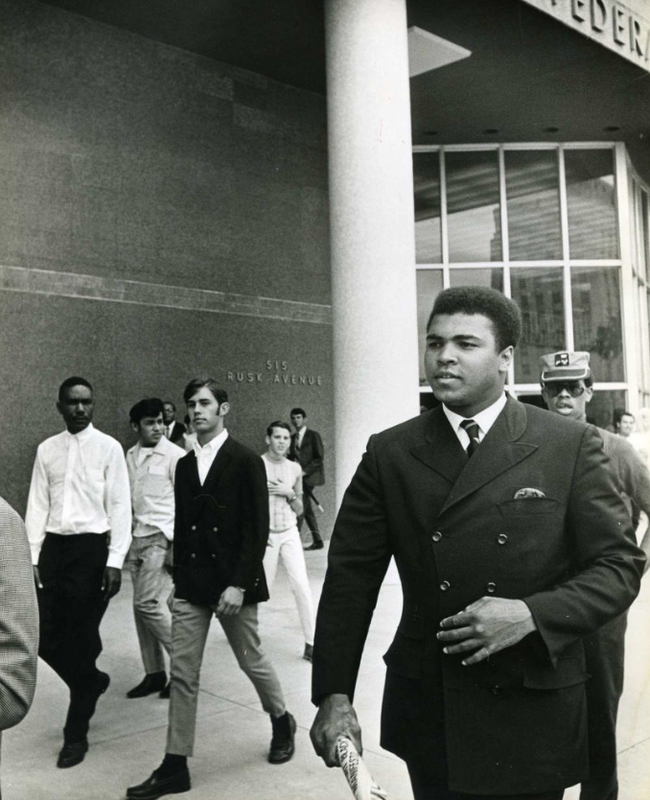

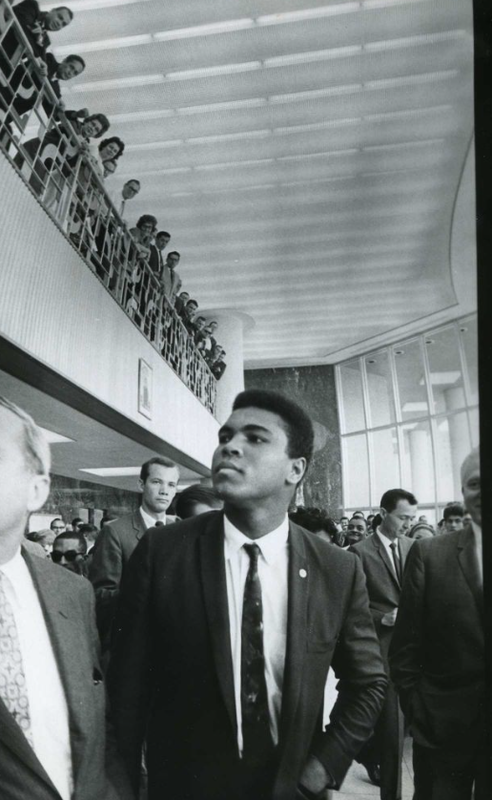

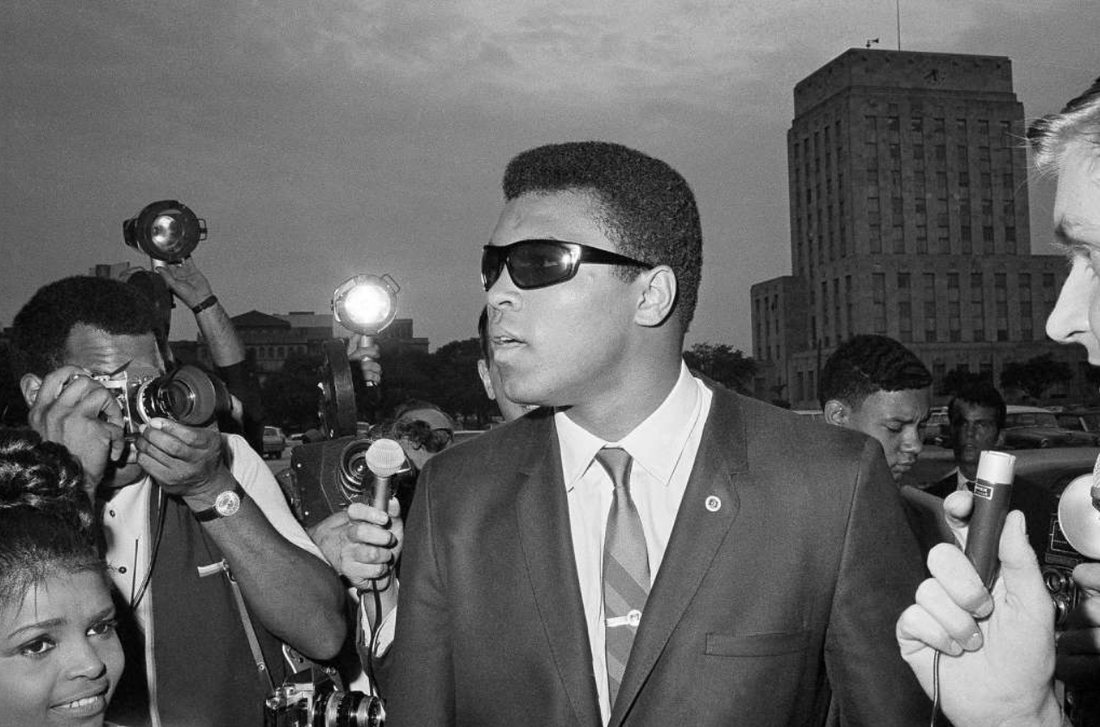

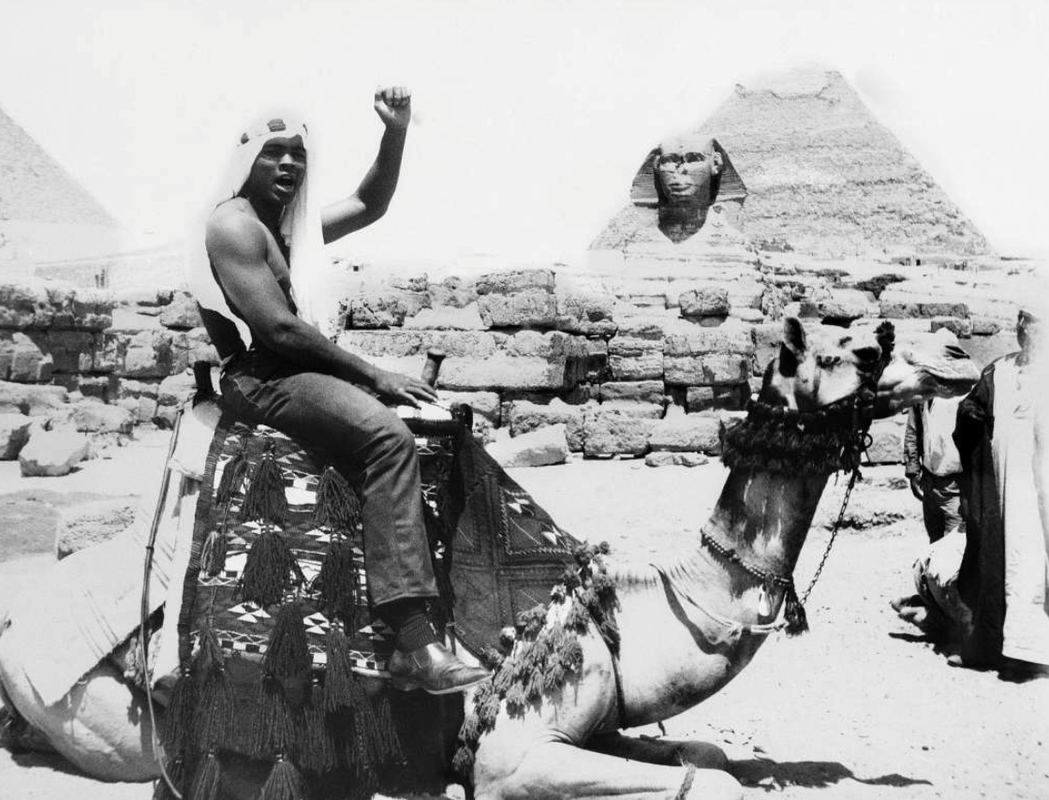

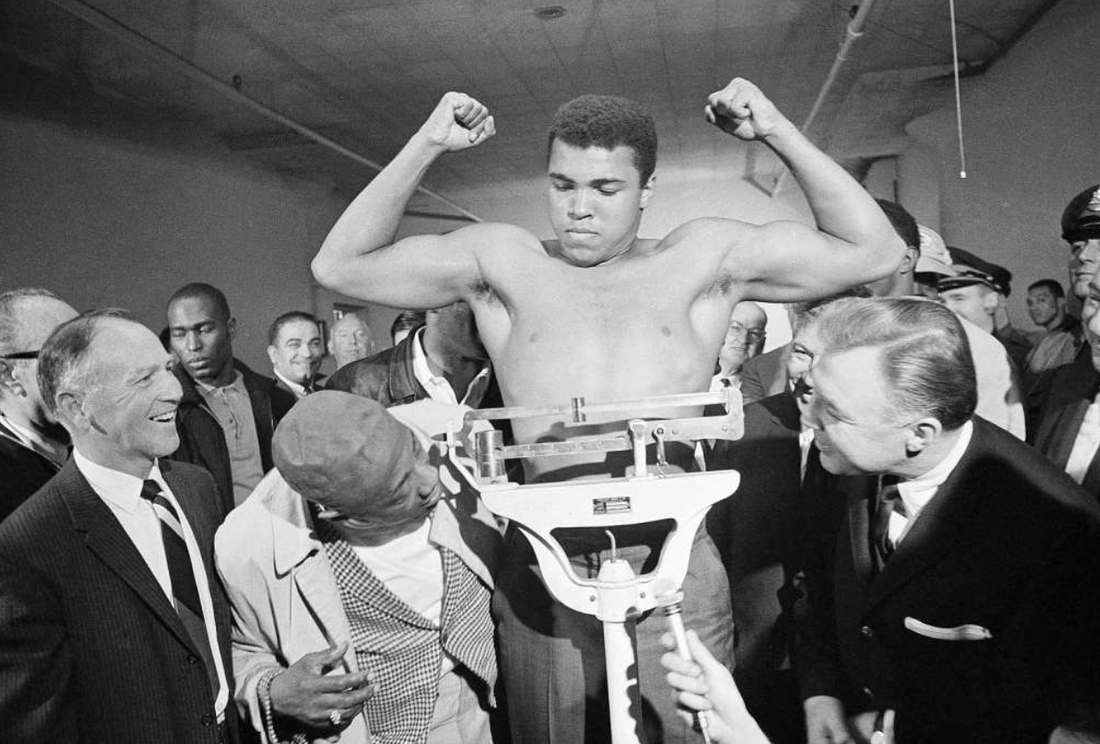

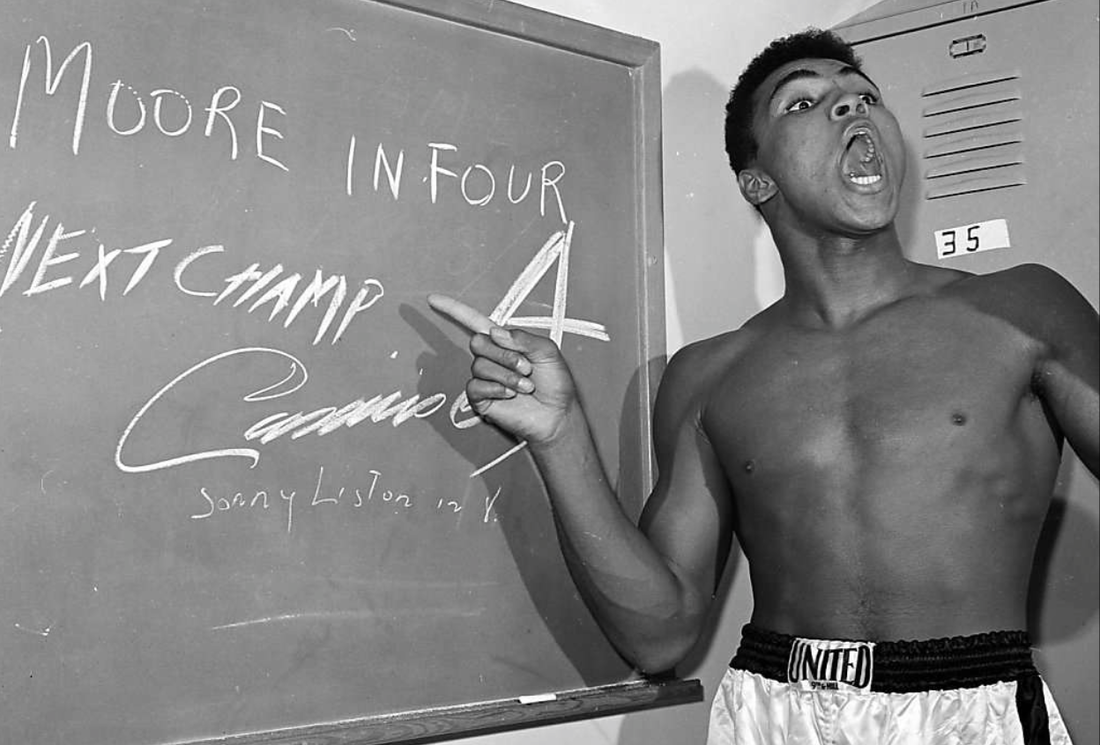

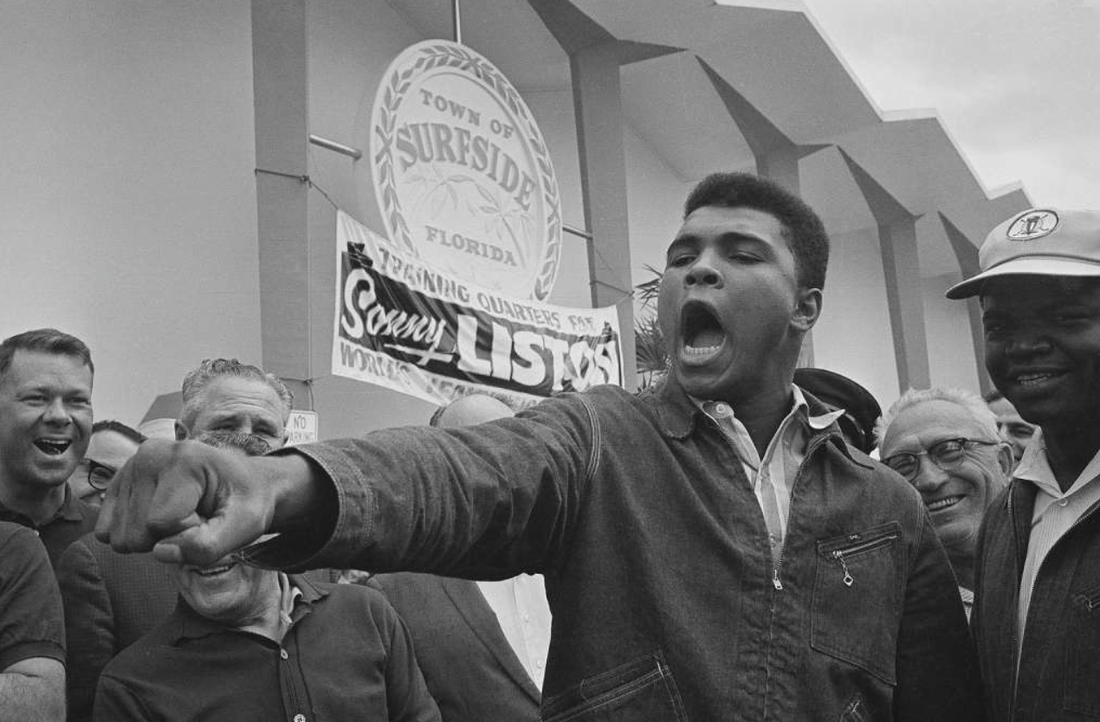

Ali was famously a person who could make a stage out of anything. Even his weigh-ins turned into acts worthy of Carnegie Hall. But on April 28, 1967, the U.S. government handed him the biggest stage of his life.

At an armed forces examining station in Houston, he refused to step forward to a white line when his name was called. That one step would have signified his willingness to be drafted.

The awesome drama of that moment made Ali hated at the time, but also turned him into a martyr to history. The symbolism of a man who made his living fighting refusing to fight was extraordinarily powerful.

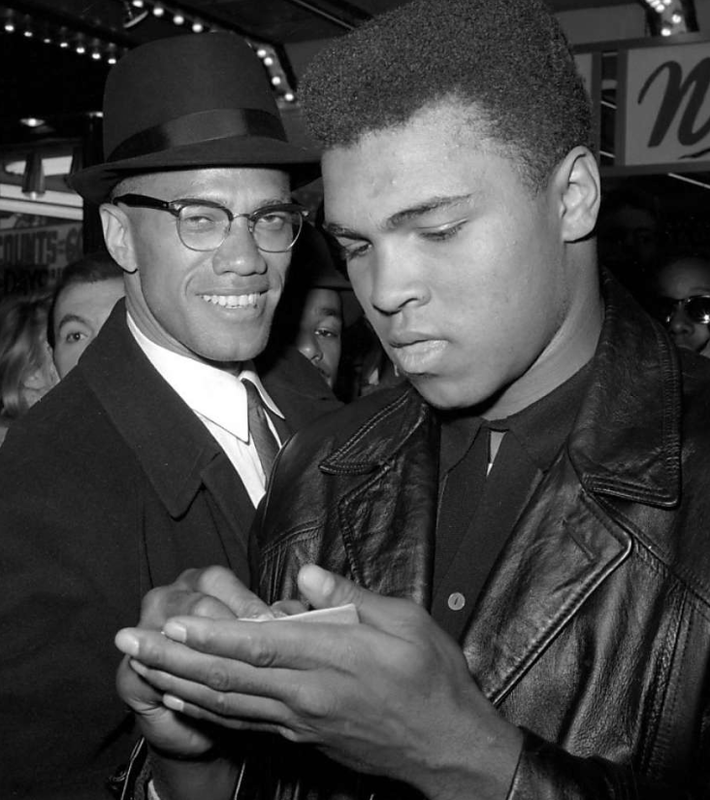

Ali furthermore brilliantly used the moment to link America's bloody quagmire overseas to the domestic warfare that had broken out in places like Watts, Rochester, Newark, Cleveland, Detroit, and Division Street, Chicago.

"My conscience won't let me shoot my brother or some darker people," Ali said. "And shoot them for what? They never called me nigger."

Asking Ali to step forward that day in Houston was an epic strategic blunder. The last thing Lyndon Johnson or his successor Richard Nixon needed was to have Americans of any age, but particularly young people, making a connection between racism at home and wars of colonial domination abroad.

But by demanding that a man as prideful and magnetic as Ali submit to becoming a cheerleader for the bloodshed in Vietnam, that's exactly what they did.

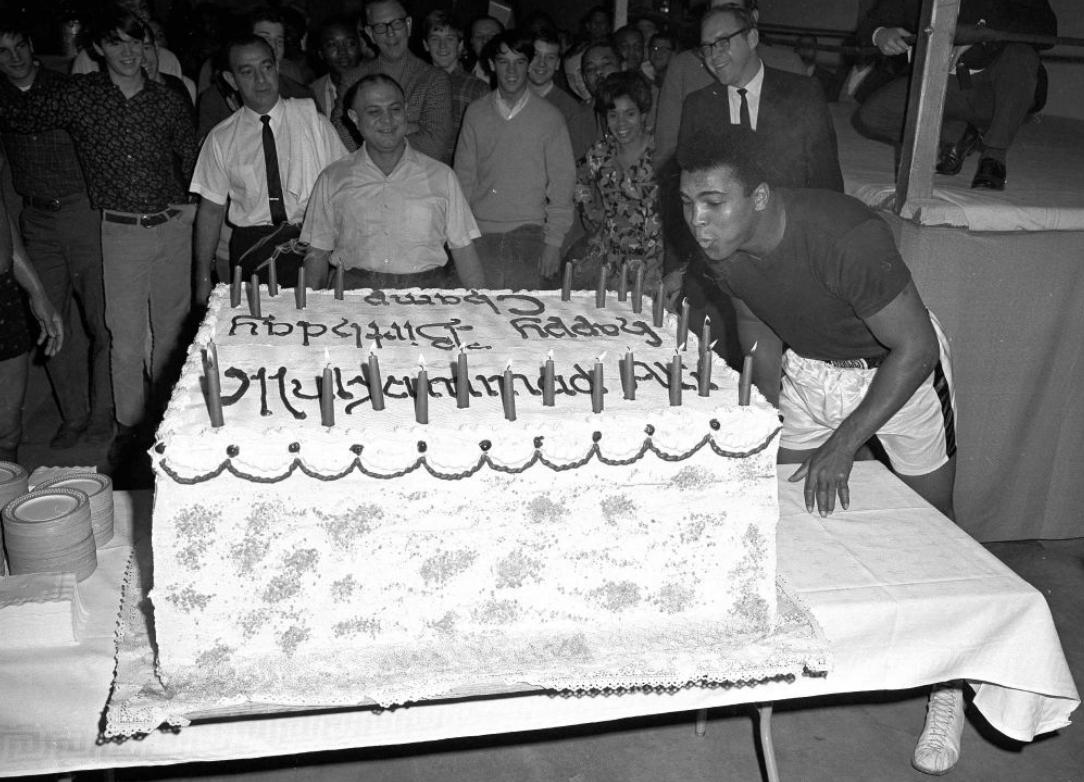

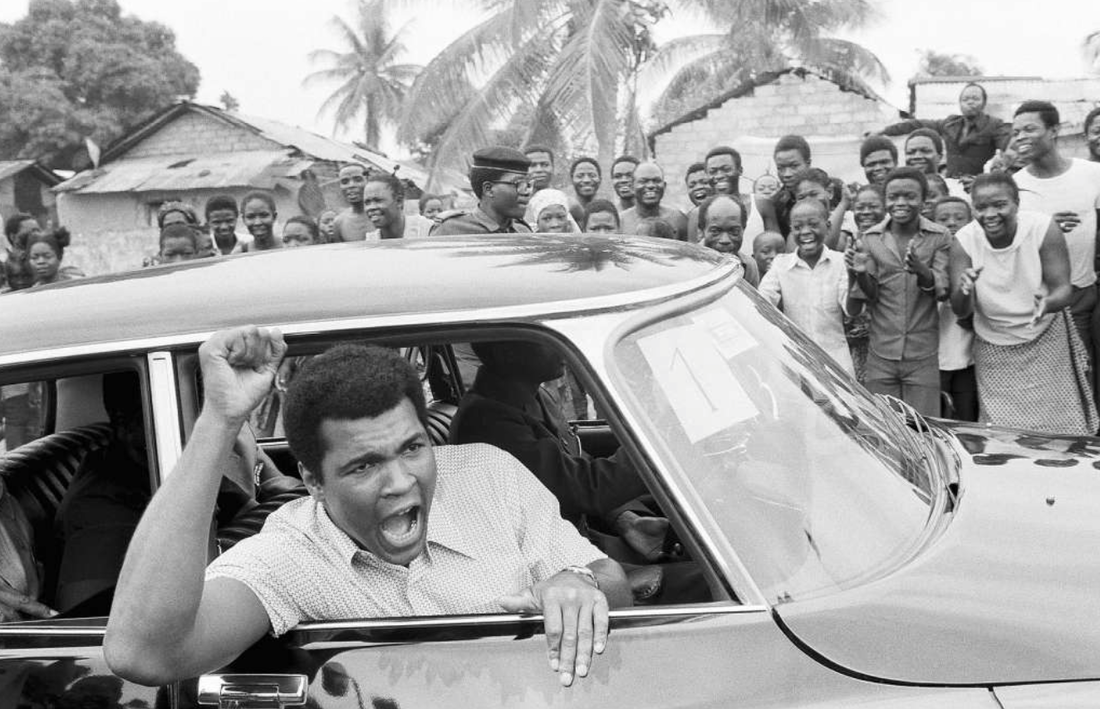

Even stripped of his title, Ali had enormous influence. He grew up in the dawn of the television age, for which his outsized personality was perfectly suited. He was one of the first people to understand the power of celebrity in the mass-media age, and became one of the first truly international media icons, more famous than JFK, Elvis, Khrushchev or the pope.

After refusing induction, Ali used that celebrity to become a dangerous and persuasive critic of the American state. Right away, he received public statements of support from people like Jim Brown, Lew Alcindor (the future Kareem Abdul-Jabbar), Bill Russell and Martin Luther King, instantly giving him credibility with young people, particularly nonwhite young people.

King, incidentally, had pivoted toward criticism of the war right around the same time that Ali was refusing induction. He gave a speech in 1967 called "Beyond Vietnam" that made a lot of the same points Ali did.

"We were taking the black young men who had been crippled by our society," King said at Riverside Church in New York on April 4th of that year, "and sending them 8,000 miles away to guarantee liberties in Southeast Asia which they had not found in southwest Georgia and East Harlem."

A year after that, unrest over the war essentially cost Lyndon Johnson his presidency. Abroad, the Tet Offensive sent American troops reeling toward a crushing defeat.

And later on, media efforts like the horrific "running girl" photo and the documentary Hearts and Minds helped confirm in the minds of large numbers of Americans a previously unthinkable idea: that the United States, savior of the world in the war against Nazism, was now the bad guy in the movie, a villain state that had murdered hundreds of thousands or even millions of poor civilian farmers for the sake of — what exactly?

The lesson the government should have learned from this disastrous episode was not to try to project power and influence by military occupation. Instead, the Pentagon saw Vietnam as a public relations failure. What military leaders thought they learned from the Indochinese fiasco is that wars are won on the airwaves as much as on the battlefield.

It's not a terribly well-advertised fact, but the Pentagon has the single largest public relations budget in the world, annually spending billions to make sure that what happened in the Sixties does not happen again.

It's being said a lot in the wake of Ali's death that his counterparts today would never make the sacrifices he made. "Today's transcendent athletes are too busy protecting their bank statements to make a political statement," is how Christopher Gasper of the Boston Globe put it.

That might be true, but it's also true that today's athletes haven't been asked to do what Ali was asked to do. Nobody is asking LeBron James to step forward to any white line. Nobody tried to draft Randy Moss or Albert Pujols to fight in Iraq. Who knows what might have happened if someone had?

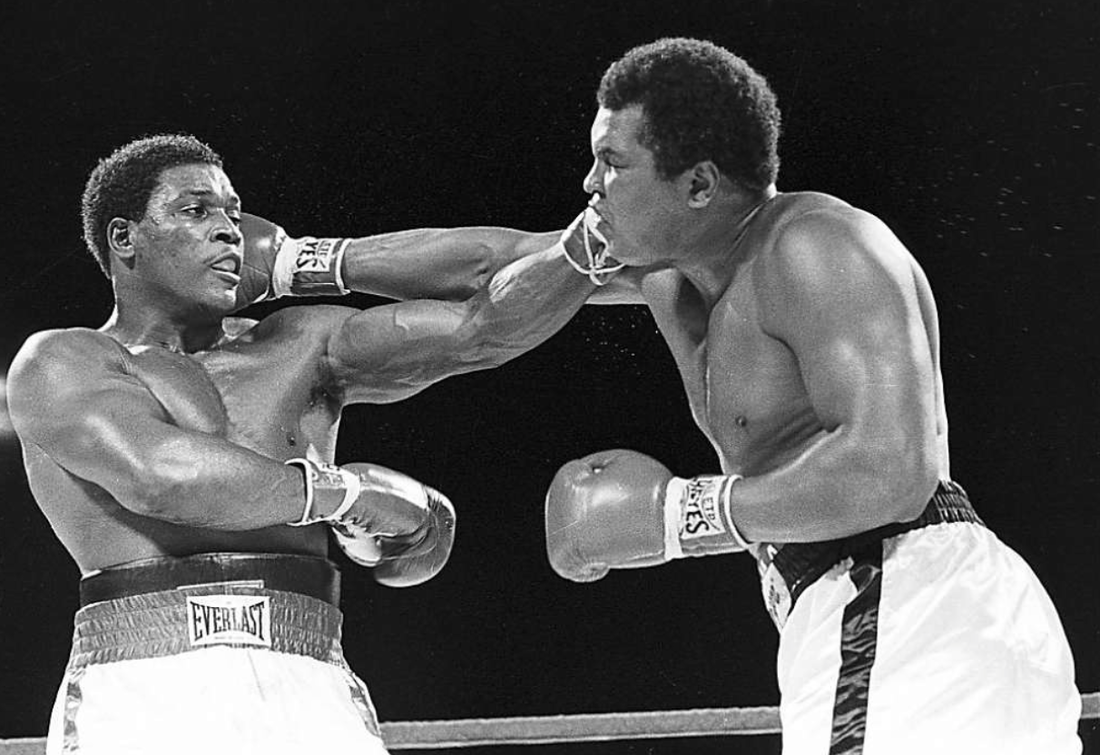

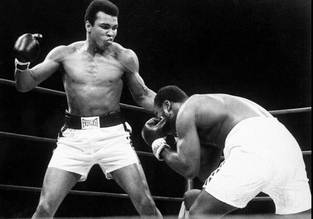

The government eliminated that variable decades ago. In 1971, just as a comebacking Ali was preparing for the "fight of the century" against Joe Frazier, Richard Nixon signed a new selective service law that led to the end of the draft and the volunteer army. No more Ivy Leaguers or mouthy celebrities would be sent off to fight. It would be mostly poor kids from farms and inner cities on the front lines from now on.

Later on, the military instituted a series of new rules governing the behavior of the press in war zones, of which the ban on photographing military coffins was only the most famous. The Pentagon tightly controlled the imagery that was sent home, making sure that our living rooms weren't filled with footage of young Americans, to say nothing of foreign civilians, being shot and mutilated.

The all-volunteer army, coupled with the new media rules, allowed America to go to war in Iraq without the same level of virulent dissent it felt during Vietnam. One of the particular successes of the new PR strategy was the near-total lack of outrage or empathy over the deaths of Iraqi civilians.

Muhammad Ali in the Sixties easily penetrated Pentagon propaganda about the enemy in the jungle by pointing out that he personally had no quarrel with the Vietnamese. He forced Americans to think about the moral consequences of killing other human beings half a world away who really had nothing to do with us, until we started herding them into "strategic hamlets."

But a generation later, we Americans mostly lack the instinct to even ponder those questions. We sit through movies like American Sniper that tell us that Iraqis are villains because they shoot at our soldiers. The question of why we were ever there in the first place to shoot or be shot at is not talked about as much.

In large part that's because the government has successfully sanitized the use of force. The brutality and ugliness of war is mostly kept separate from pop culture. Wars look like video games to young people today. This isn't an accident. It's the result of billions of dollars of research and propaganda devoted to the problem of preventing the wholesale attacks of conscience that broke out during the Sixties.

Ali wasn't a perfect person. His cruel treatment of Joe Frazier in the runup to their three epic fights is a particular stain on his legacy. That Ali himself came to understand this only slightly diminishes the fact.

But he was still a hero, flaws and all. He would have been larger than life anyway, but his defiant stand against his own government amplified his legend as a fighter of bottomless will and courage, and made him a towering figure in our history.

When he's laid to rest later this week, most people will remember how much he was beloved for those qualities. But let's not forget that not everyone loved him, or found him and his defiance so charming. His detractors have a legacy as well, one that sadly enough might outlast his.

-

-

Very definitely, the greatest...

"may he rest in peace"